July 22, 2025 • 24 min read

NIST Incident Response Guide: Lifecycle, Best Practices & Recovery

Vice Vicente

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is perhaps best known for establishing rigorous and robust standards for cybersecurity through the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF). In August 2012 they released the Computer Security Incident Handling Guide (NIST Special Publication 800-61 Revision 2), geared towards responding to IT security incidents. While NIST is not a regulatory entity, its research into cybersecurity planning and risk management has led them to develop rigorous protocols for recording, reporting, and responding to breaches and incidents. NIST SPs offer thought leadership and guidance addressing specific areas like incident management and effective incident response.

It’s no exaggeration to say that incident response is one of the key areas of IT risk and security today, and one of the most complicated. With cyberattacks coming from innumerable vectors in real-time, the risk of internal malicious or negligent activity, and vulnerabilities emerging in many information systems, it seems inevitable that a company will run into an incident like a data breach. The key then, is how prepared your organization is to detect, respond, and remediate incidents and their root causes, and how well your organization uses past insights to prevent future incidents.

Read on to learn how you can follow the NIST incident response guidelines to lower costs, avoid liability, develop an incident response plan, and keep your clients’ data secure.

What Is NIST Incident Response?

NIST released the second revision of their Computer Security Incident Handling Guide in 2012, which treats the phrase “incident response” as interchangeable with “cybersecurity incident response.” An incident response plan is a systematic process that an organization can use to predict, plan for, and handle a cybersecurity incident. The process is also iterative, since actually encountering cybersecurity incidents will strengthen the process and help to tighten systems and avoid further incidents in the future. An incident response plan can leverage incident response frameworks, like the methodology presented by NIST and other standards organizations. SANS, an institute dedicated to information security thought leadership and education, also provides instruction on performing effective incident response in their courses.

An incident response process or procedure usually applies to a single type of incident, since there are many, many incident categories that exist. Incident response procedures are tailored to specific types of categories or events, like what to do if you have fallen victim to a phishing or social engineering attack, or how to isolate and eliminate malware from an infected server. When similar incidents can be addressed through an existing response process, those types of incidents can be consolidated. Since incidents may require team members from different business units to collaborate, it’s important to incorporate escalation paths and responsibilities into your incident response process documentation.

The NIST framework and guide is comprehensive and includes a checklist to prepare for security events that can be used as you build your own audit checklist. The 2012 update to the Cybersecurity Incident Handling Guide also offers an extended section on how to share information between organizations in the case of a cybersecurity threat. Sharing information about cyber threats is one of the indicators of a mature cybersecurity program, and benefits the larger security community.

NIST’s guide on incident management and response includes sections that outline:

- Cybersecurity and incident handling best practices.

- Definitions of incident response and other terms and concepts.

- Requirements and best practices for developing incident response policies, plans, and procedures.

- Incident response team models, roles, and responsibilities.

- Information sharing recommendations regarding the media, law enforcement, and other organizations.

- Incident scenarios for tabletop exercises (TTX).

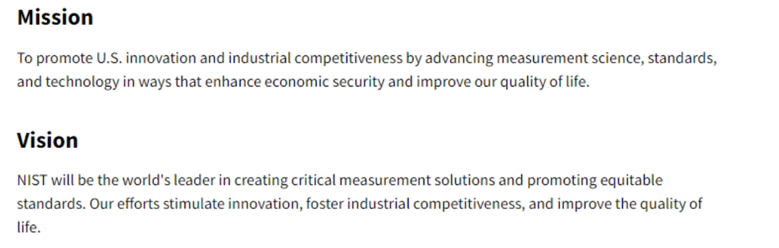

Why Is NIST Providing Recommendations on Incident Response?

NIST developed its guidelines on incident response in an effort to help federal agencies, businesses, and non-governmental organizations prepare for cybersecurity incidents; the guidelines are designed to help organizations respond to incidents to have a common framework to handle cybersecurity incidents, promoting consistency and reliability in response efforts. Furthermore, NIST’s incident handling guide is technology-agnostic, and compatible with the NIST CSF, meaning that this guidance can be applied to any type of information system, regardless of hardware, software, operating systems, protocols, or applications.

Under the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA), NIST is obligated to provide recommendations to federal agencies, as these agencies are required to demonstrate their incident response capability. Also FISMA mandates continuous monitoring of information systems. NIST 800-61 contributes to this by offering guidelines on maintaining situational awareness and improving detection capabilities, which are crucial for continuous monitoring.

The combination of NIST’s mission and vision, plus the requirements put forth by FISMA in 2014, provided impetus for the release of NIST’s Cybersecurity Incident Handling Guide.

Image: NIST’s Mission and Vision

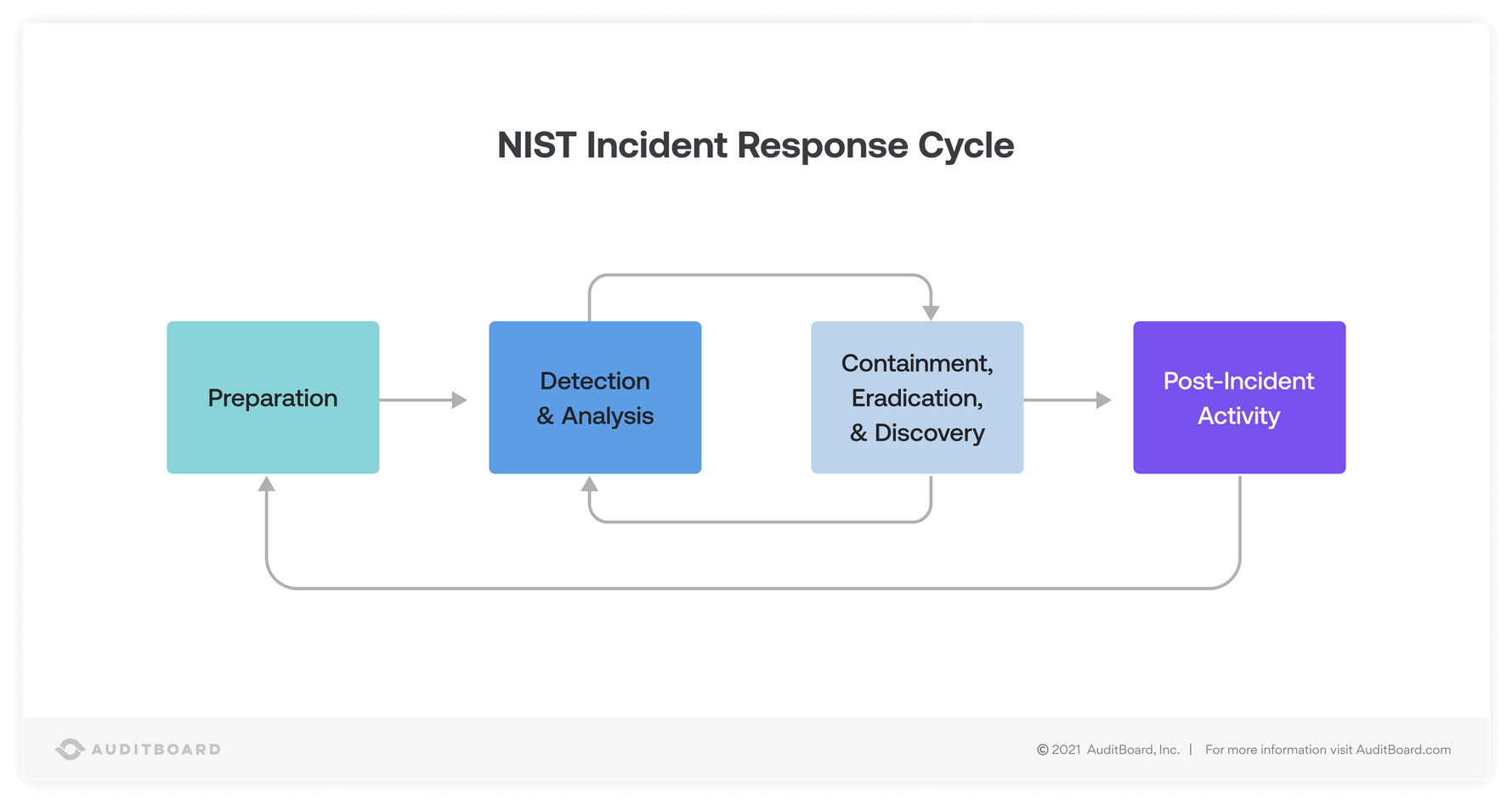

What Does the NIST Incident Response Lifecycle Look Like?

NIST’s incident response lifecycle has four overarching and interconnected stages: 1) preparation for a cybersecurity incident, 2) detection and analysis of a security incident, 3) containment, eradication, & recovery, and 4) post-incident analysis.

What are the Four Parts of the NIST Incident Response Cycle?

The four components of the NIST incident response cycle in order are: preparation, detection and analysis, containment, eradication, and recovery, and post-incident activity. Each phase has a goal and role in incident response.

1. Preparation

The “Preparation” stage of the NIST Incident Response lifecycle focuses on the implementation of an incident response policy and function and the prevention of cybersecurity incidents. Preparing for and preventing incidents can be daunting when you haven’t already encountered the threat and don’t yet know the full shape of it. In preparing for a cybersecurity incident, NIST suggests implementing a series of tools ahead of time, so that you are ready to analyze, isolate, and respond to an incident. These include securing communication tools and facilities for the on-call personnel that will be handling the critical incidents if they occu or, from having contact information readily available for stakeholders and reporting entities, to purchasing smartphones for your Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT), to having space available for your “war room” where the team can gather and manage the crisis. This can also ensure the availability of necessary tools and resources, such as forensic software, monitoring tools, and communication mechanisms.

While this particular NIST Special Publication does not cover the specifics of securing information systems, it does emphasize the importance of prevention as part of incident management. Preventing events and incidents comes down to securing your IT environment and monitoring your systems and network continuously to detect any anomalies. NIST recommends the following practices for securing your systems and preventing incidents:

- Conduct periodic risk assessments and corresponding mitigation efforts to understand your IT risk environment.

- Apply system and server hardening best practices and configurations to IT infrastructure.

- Secure your network perimeter and deny unauthorized access.

- Utilize anti-malware and anti-virus software to protect company assets.

- Train users in policies, procedures, security awareness, and appropriate use of IT assets.

Preparation is the first step in the NIST incident response process, andcan occur throughout the incident management lifecycle. Upgrading security capabilities, utilizing automation to streamline controls, and establishing a baseline for system performance and network traffic can all be considered part of the preparation phase, but can be done even as other steps of the incident handling process are happening concurrently.

2. Detection and Analysis

The detection and analysis stage requires first identifying the type of threat you’re facing and determining whether or not it is an incident. NIST provides a list of potential threat types and divides the signs of an incident into two categories: precursors and indicators.

A precursor is a sign an incident may occur in the future, and an indicator is a sign that an incident may be occurring at present or has already occurred. An example of a precursor event would be a hacker group notifying an organization that they plan to attack them. An example of an indicator could be the detection of anomalous activity in a privileged server. Unfortunately, most signs of an attack are only visible after an attack has already begun, but an organization with a mature incident response capability may be able to detect precursors and prevent an attack before it begins. Using automated tools, such as intrusion detection systems (IDS) and security information and event management (SIEM) systems help to identify such potential incidents.

Most companies will likely be dealing with indicators; these will guide you in determining where the attack is coming from, how to contain it, and how long you have to continue to gather evidence. Some techniques security team members can use to analyze an incident include:

- Obtain familiarity with the IT environment and normative behavior to facilitate detection of anomalies.

- Set a log retention policy and maintain logs across various systems, as incident information can be captured in different places and systems.

- Map events across systems to gain a complete picture of the extent of the security breach, incident, or event.

- Synchronize server clocks to keep logs accurate.

- Establish a knowledge base for incident handlers to reference easily.

- Use scanning technologies, like packet sniffers, vulnerability scanners, and dependency scanners to collect data.

Incident analysis doesn’t stop at identification; rather, this phase of incident response encompasses incident documentation and prioritization as well. Documentation is the backbone of security, risk, and compliance, and this holds true for incident management. Incidents should be documented in some kind of ticketing system/issue tracking system or repository, with all statuses and activities related to that incident captured in the ticket. Creating incident response templates can facilitate this activity, and ensure that all necessary data is captured.

Incident prioritization involves assessing open incidents for their impact and recoverability, and making decisions based on the needs of the business. Depending on the size of the business and the industry, a company can experience many incidents at once. That company may not have all the resources needed to tackle all open incidents at the same time, thus prioritization is needed.

Finally, this part of the cycle also includes properly reporting a cybersecurity incident internally, to the appropriate agencies, law enforcement, and/or other affected parties.

3. Containment, Eradication, and Recovery

Containment, eradication, and recovery make up the bulk of active incident response. This stage of incident response includes isolating the threat and affected systems to make sure it does not proliferate; however, NIST documentation is clear that the containment strategy must match the type of attack and the potential damage incurred if the attack continues. This will require you to implement a long-term and a short-term containment strategy to limit the impact. Moreover, merely disconnecting the attacking host from the data source may backfire; NIST suggests that the incident response team have a specific containment plan for each type of attack they anticipate based on risk assessments and analyses. This phase also includes identifying and researching the attacking host and gathering evidence that can be used in legal matters; NIST suggests that in some cases the response team may choose to use a “sandbox” to contain the threat in order to encourage the attack to continue so the team can gather more data, but this strategy carries risks.

Once contained, your cybersecurity team can work on eradicating the threat, including removing malware and deleting compromised accounts. Finally, the team can move to a phased recovery, where the organization can resume with normal operations. Recovery may include cybersecurity patches, taking steps to improve firewalls, reinstalling anti-malware and anti-virus software, restoring systems from clean backups, and changing passwords across the organization. In containerized environments, recovery might also mean spinning up new functions and virtual machines from a template. This may also include rebuilding systems, and conducting thorough testing to ensure systems are free of threats.

In containerized environments, recovery might also mean spinning up new functions and virtual machines from an image template.

4. Post-Incident Activity

NIST says that the “Post-Incident Activity” step is the most often omitted and the most important — after the incident, the team should hold a “Lessons Learned” meeting to process the incident, go over strategies for preserving the data collected and evidence gathered over the course of the meeting, and revisit preparation for future cybersecurity threats.This will require you to thoroughly document the incident, including how it was detected, the response actions taken, and the impact on the organization. Once an organization has established baselines and metrics for its incident management program, these data points can be used in the future to evaluate the CSIRT’s performance and make sure the incident response function is performing as anticipated.

This phase also includes creating a follow-up report on every part of the incident. This report can be used for internal purposes, and can also be shared with external organizations. This will require the organization to implement changes based on the lessons learned, such as updating security controls, enhancing monitoring, and providing additional training. Managing and preventing cybersecurity threats often goes beyond a single organization and requires cooperation and mutual involvement across the entire incident response cycle. NIST and other standards and cybersecurity organizations encourage the sharing of security knowledge among companies and institutions, especially since cyber criminals do the same.

Do You Need an NIST Incident Response Team?

The NIST recommends having a Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT), either in-house or through a third-party Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC). This team will include IT and cybersecurity experts, but may also engage public relations and legal experts. Depending on the scale and cybersecurity needs of your organization, you may choose to hire professionals to be available immediately and onsite; if your organization has overwhelming security needs, like Facebook or Amazon, then your team will be full-time and available 24-7.

For many organizations however, hiring full-time IT staff to respond to incidents is not particularly cost-effective. The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre states that “it is more cost-effective to have a ‘virtual’ CSIRT, pulled together when needed, from people who have other day jobs.” NIST states that organizations that do not have contact with a CSIRT “can report incidents to other organizations, including Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs)… industry-specific private sector groups [which] share important computer security-related information among their members.”

CSIRTs or just IRTs (Incident Response Teams) often develop organically along with the company. Small businesses with limited budgets and personnel may need to take the ad-hoc route, convening key team members for incident response when needed. In those cases, even the CEO or founder might be part of that IRT. In either case, the organization has to ensure that the IRT is well-trained and up-to-date on the latest threat landscapes and response techniques. Enterprises and other large organizations may find that they need a dedicated CSIRT to cope with the volume of incidents occurring in their environment. In such cases, internal and hybrid approaches tend to work very well. In a hybrid approach, an organization would work with their internal IRT and supplement that team’s capabilities with external resources. Fully outsourced IRT functions can also do the job. That said, many times incident response requires elevated access to privileged systems to complete containment, eradication, and recovery. In those cases, it can be very helpful to have an internal team member with access to the affected systems to assist outsourced IRTs.

In short, having a formal or ad-hoc incident response team is highly recommended, but how that team is formed, who it’s composed of, and how it’s called into action will differ from company to company.

NIST Incident Response Takeaways

NIST’s strategies for incident response and their vision for the incident response cycle are some of the best available guidance for IT management teams,the CIOs, and the CISOs seeking to protect their organization from costly, reputation-damaging cybersecurity events and figuring out how to prevent cybersecurity breaches. NIST argues that incidents are just part of the IT landscape, and we may not be able to avoid them entirely, but we can certainly minimize their impact on our businesses and lives to bring down the risk to an acceptable level. If your team wants to be prepared for a potential cybersecurity event, AuditBoard’s compliance management software can help you keep track of NIST’s incident response guidelines and ensure that you have a central hub for your CSIRT to access relevant documentation, logs, and incident-related information.

Frequently Asked Questions About NIST Incident Response

What is NIST Incident Response?

An incident response plan process is a systematic process that an organization can use to predict, plan for, and handle a cybersecurity incident. NIST incident response methodology outlines steps and best practices for an incident response function.

Why is NIST providing recommendations on Incident Response?

The combination of NIST’s mission and vision, plus the requirements put forth by FISMA in 2014, provided impetus for the release of NIST’s Cybersecurity Incident Handling Guide.

What are the four parts of the NIST Incident Response Cycle?

NIST’s incident response lifecycle cycle has four overarching and interconnected stages: 1) preparation for a cybersecurity incident, 2) detection and analysis of a security incident, 3) containment, eradication, and recovery, and 4) post-incident analysis.

Do you Need a NIST Incident Response Team?

In short, having a formal or ad-hoc incident response team is highly recommended, but how that team is formed, who it’s composed of, and how it’s called into action will differ from company to company.

What is new in NIST SP 800-61 Revision 3?

SP 800‑61r3 (April 2025) aligns incident response with the NIST CSF 2.0 risk management functions, emphasizes continuous improvement, and offers a flexible, ongoing response model over static cycles.

Why integrate incident response into risk management?

Embedding incident response in the broader cybersecurity framework makes it proactive, scalable, and aligned with governance—and supports better detection, response, and recovery.

About the authors

Vice Vicente started their career at EY and has spent the past 10 years in the IT compliance, risk management, and cybersecurity space. Vice has served, audited, or consulted for over 120 clients, implementing security and compliance programs and technologies, performing engagements around SOX 404, SOC 1, SOC 2, PCI DSS, and HIPAA, and guiding companies through security and compliance readiness. Connect with Vice on LinkedIn.

You may also like to read

What is the Colorado AI Act? A detailed guide to SB 205

What is the EU AI Act?

What is the NIST AI Risk Management Framework?

Discover why industry leaders choose AuditBoard

SCHEDULE A DEMO